Irish-born journalist William H. Brayden in the summer of 1925 wrote a series of articles for US newspapers about the newly partitioned Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. This summer I am revisiting various aspects of his reporting. Read the introduction. Brayden’s coverage of the Irish Boundary Commission is divided into two posts. Part 2 begins below the map. Read Part 1. MH

This map of the 1921 border between Northern Ireland (Ulster) and the Irish Free State also showed “probable” and “doubtful” changes proposed by the Irish Boundary Commission. It was leaked to the Morning Post, London, which published the map and narrative descriptions on Nov. 7, 1925.

After years of delay, the Irish Boundary Commission in spring 1925 was finally engaged with deciding whether to adjust the 1921 border that separated the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland, then more often called Ulster. The three-member commission held hearings in several border towns. But the commission chairman quickly ruled out allowing these communities to decide by referendum if they wanted to remain under their present government or switch to the other side, as Free State nationalists hoped.

As the commission’s deliberations continued into summer 1925, Brayden opened his US newspaper series by explaining to American readers the differences in home rule government on each side of the border. The Free State could impose and collect taxes; levy tariffs; establish its own currency (that happened in 1928); send ambassadors to foreign states and make international agreements. Street signs and public documents now were written in Irish as well as English. A new police force, Garda Siochana, replaced the Royal Irish Constabulary. The judiciary was made over from the established British legal system and Sinn Fein courts of the revolutionary period.

US newspaper map of divided Ireland in 1925 … and today.

Dublin Castle, once the seat of the British administration in Ireland, was transformed into the home of the new court system. Leinster House, the former ducal palace and headquarters of the Royal Dublin Society, became the new legislative headquarters. The Irish tricolor waved above these and other buildings instead of the British Union Jack. On the streets below, postal pillar boxes were painted green instead of red.

The Free State’s “separation from England, apart from constitutional technicalities, is practically complete,” Brayden wrote. By contrast, Northern Ireland was “not a dominion,” like the Free State and Canada, and had “a subordinate and not a sovereign parliament.”

Postal, telegraph, and telephone services remained regulated by London. The northern legislature was prohibited from taking action on trade and foreign policy matters. “Nevertheless, home rule in north Ireland is very real and can be, and is, effectively used for the development of local prosperity,” Brayden wrote.

Irish republicans at the time, and historians today, would argue the Free State’s separation was not as “practically complete” as characterized by Brayden. Others could make the case that Northern Ireland, which retained representation in London, was not as subordinate as Brayden described. But there was no argument that the island of Ireland had been divided.

Religion, and money

Most Americans would have had at least general knowledge of the history and geography of division between Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics. Brayden mostly avoided the sectarian issue in his series. In one story he sought to minimize “the once familiar catch phrase that ‘home rule must mean Rome rule’ ” by informing readers that several Free State high court justices were Protestants, while the lord chief justice of Northern Ireland was a Catholic. In another story, however, he conceded the Irish educational system was “strictly denominational” on both sides of the border.

But something larger than religion or politics loomed over partition and the boundary commission–money. Specifically, how much of Great Britain’s war debt and war pensions the Free State was obligated to pay. Like the boundary commission, this was another aspect of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty that remained unsettled four years later. It was complicated by whether the Free State could offset the amount, or even be entitled to a refund, by considering historic over-taxation by London.

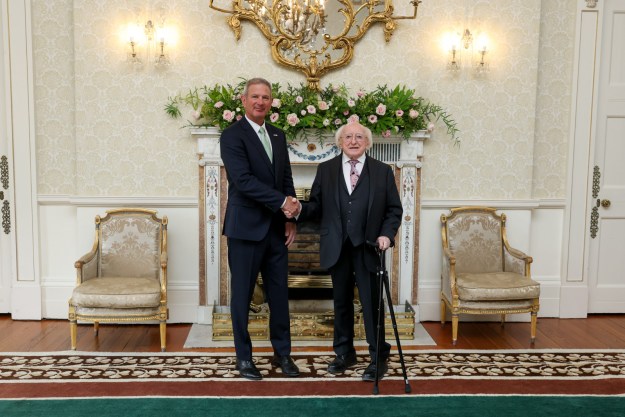

William Brayden, undated.

“The view widely held in [Free State] Ireland is that the Irish counterclaim will wipe out, and even more than wipe out, the British claim,” Brayden reported. He revealed that the late Michael Collins, killed in 1922, “was clearly of opinion that something was due. I heard him urge that the amount, when ascertained, be paid off in a lump sum, rather than by annual payment that would wear the appearance of tribute.”

But it was impossible to resolve such financial questions until the boundary between the Free State and Northern Ireland was finalized. “Twenty-eight counties would pay, or receive, more than the present twenty-six,” Brayden wrote.

Referring back to his early 1922 reporting (See Part 1), Brayden speculated, “real trouble may arise” if the commission awarded the “storm centers” of Derry or Newry to the Free State. Nevertheless, officials in the south no longer believed “that any possible adjustment of the boundary would ever leave the northern government so hampered that it could not continue its separate existence and would be obliged at last to come into the Free State,” Brayden wrote.

“The continued existence of the northern government is now regarded as certain. Wherever the boundary line is drawn it will still divide Ireland into two parts with two separate governments.”

As regrettable as partition was, Brayden continued, many Irish citizens were more concerned about poor trade, high unemployment, and insufficient housing. “Many causes have combined to make the boundary issue less critical than it was a year ago,” he wrote. “Active feeling regarding it will not revive until the commission has reported. Meanwhile, there is little or no protest against the delay which the commission is making.”

What happened

In early November 1925, the Morning Post, a conservative daily in London, published details and a map from the Irish Boundary Commission’s deliberations. The leaked documents showed the commission recommended only small transfers of territory, and in both directions. Though Brayden and others had reported the Free State abandoned the idea of making large land gains from the north, the Post story, once confirmed, embarrassed the southern government.

Details of the Irish Boundary Commission report were leaked to the Morning Post, London, which published this story on Nov. 7, 1925. (Library of Congress bound copies of the newspaper, thus the curve to the image.)

“The result is described as a bombshell to Irish hopes, and all agree that the establishment of the boundary line indicated by the commission would make more trouble than by maintaining the present line,” Brayden reported in a regular dispatch, now four months after his series concluded. The Free State would receive only “barren parts of [County] Fermanagh” while Northern Ireland stood to gain “rich territory in [County] Donegal.” The Free State’s representative, Eoin MacNeill, quit the commission. “In the border districts passions are high” among nationalists who hoped to join the Free State.

A series of emergency meetings between the Free State, Northern Ireland, and the British government were held in London through early December. The three parties quickly agreed the existing border should remain in place. The Free State’s obligation for war debt and pensions would be erased in exchange for dropping the taxation counterclaim. The Free State would have to assume liability for “malicious damage” during the war in Ireland since 1919.

“Maintenance of the existing Ulster boundary is welcomed as avoiding a grave danger to peace,” Brayden reported after the settlement. Northern nationalists “are advised by their newspapers in Belfast to make the best they can of their position in the northern state.” while “die-hard Ulster newspapers call the result a victory for President Cosgrave.”

The Morning Post, which detailed the leaked border proposal a month earlier, also criticized the settlement as “a surrender of a British interest with nothing to show for it but the hope of peace. … We think the British public would be appalled if they were to see arrayed in cold figures the price we have paid and are still paying for the somewhat questionable privilege of claiming our hitherto unfriendly neighbor has a Dominion when the substance and almost the pretense of allegiance have ceased to exist.”

Cosgrave conceded that Northern nationalist Catholics would have to depend on the “goodwill” of the Belfast government and their Protestant neighbors. Similarly, Brayden quoted an unnamed unionist member of parliament as saying, “Good will should take the place of hate. North and south, though divided for parliamentary purposes, can be of assistance to each other and in the interest of both more cordial relations should exist.

US Consul Charles Hathaway and other US officials were generally pleased by the outcome. The Americans believed the agreement stabilized the Free State financially and avoided potential irritation to US relations with Great Britain. They also realized that Éamon de Valera and Irish republican hardliners, as well as the always volatile sectarian issue, still threatened the peace in Ireland.

The “high explosives” that Hathaway had worried about in 1924 reemerged periodically throughout the twentieth century, especially during the last three decades. “Goodwill” in Northern Ireland turned out to be in short supply.

One final note: the public release of the commission’s work was suppressed by agreement of all three parties in December 1925. The documents remained under wraps until 1969, just as the Troubles began in Northern Ireland.

See all my work on American Reporting of Irish Independence, including previous installments of this series about Brayden.