Milton Bronner’s “extensive trip up and down the western counties of Ireland” in February 1925 covered the most forlorn districts of the island at the bleakest time of the year. He came to investigate whether famine had also visited these remote parts of the three-year-old Irish Free State.[1]”Erin Revealed As Suffering Hunger’s Pangs”, Bangor (Maine) Daily Commercial, Feb. 24, 1925. Such a frightening possibility fell within the lifespan of those who remembered the mid-nineteenth century collapse of Ireland’s most important food staple, the potato.

Near Galway, the American journalist entered one of the “usual shanties of this coast—stone walls, badly thatched roof, one room 20 by 10 feet; its door open so light could penetrate; the floor bare, rocky earth.” There, he listened to the lament, “in curious sing-song English,” of Mrs. Bartley Connelly, the mother of eight children:

And the black rain fell. All day and every day. All spring it fell and all summer and all the rest of the year. Always the rain, the dull roar of it. Sorrow and sorrow’s sorrow. The potatoes were washed away or rotted. And the turf melted away with the wetness. No food for the pot. No turf for the fire. Emptiness and blackness in the house. And the children cryin’ because of the hunger and cold.[2]This passage was edited shorter in some newspaper presentations of the story. Bronner reported that Bartley Connelly, the 45-year-old husband and father, was working as a farm laborer and away from … Continue reading

This photo of a mother and two children–not the Connelly family–appeared in newspapers that syndicated Martin Bronner’s 1925 series about privation in the west of Ireland. Waco (Texas) News-Tribune, Feb. 23, 1925.

This was the scene-setter for the first installment of Bronner’s three-part series about privation and poverty in the rural west of Ireland. The Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) syndicated his stories to its more than 400 member publications in the US and Canada.[3]The 1925 Ayer & Son’s directory listed more than 22,000 periodicals in North America and US territories, including 2,465 daily newspapers. It is unclear how many NEA subscribers published … Continue reading February 1925 marked the peak of what has since come to be known as Ireland’s “forgotten famine,” an episode remembered today by a Wikipedia page. The entry cites Irish historian and podcaster Fin Dwyer’s 2014 piece in TheJournal.ie, among other sources.

Bronner had spent half of his 50 years as a newspaper man, working his way up from reporter to editor of the small daily in Covington, Kentucky, his native state, to NEA’s London-based correspondent since 1920.[4]”Milton Bronner, Reporter Retired Since ’42, Dies After Long Illness”, (Louisville, Ky.) Courier Journal, Jan. 7, 1959. He came to my attention in a 2023 RTÉ piece by Noel Carolan, which focused on international coverage of Ireland’s 1925 food crisis. Bronner’s series and other foreign press forced the Irish government to give more attention to the problem, which it earlier had minimized. It also prompted limited external support to the suffering residents, though nothing near the scale of the American Committee for Relief in Ireland effort of 1921.

As Carolan details, Bronner’s series was more impactful because of the “persuasive photojournalism” that accompanied the narrative. Lighter cameras with faster shutter speeds introduced in the 1920s were beginning to revolutionize news photography.[5]Library of Congress prints and photographs : an illustrated guide. [Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1994], 32. Images of faraway people and places were still a novelty to American newspaper readers a century ago. But the photographer who joined Bronner in the west of Ireland was not named in the newspapers that published these images, at least not those available for review in digital archives. Carolan did not address the mystery photographer. Nothing in Bronner’s 1959 news obituary suggests that he might have taken photos to support his reporting in Ireland or elsewhere. Readers are encouraged to provide information about the photographer’s identity—perhaps an Irish or British stringer hired for the job.

Bronner’s visit to Mrs. Connelly’s cabin was not his first trip to Ireland. In the summer of 1920 he reported on sectarian riots in Belfast and interviewed Arthur Griffith in Dublin as the war of independence approached a crescendo of violence. After the July 1921 truce he covered the London negotiations between Sinn Féin representatives and the British government that resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. Bronner was back in Ireland the following month for the handover of Dublin Castle and other government buildings from British authorities to the new Irish Free State. He interviewed Free State leader Timothy Healy for a series of dispatches at St. Patrick’s Day 1923 as the country struggled to end its civil war. Bronner interviewed Williams Cosgrave in December 1924, just two months before his trip to the western counties.[6]These stories appeared in various US and Canadian newspapers that published NEA’s syndicated content. Search results from Newspapers.com archive.

Bronner was certainly moved by the lilting brogues, “wretched” housing, and barefoot children of Mrs. Connelly and others he met and interviewed. But he was hardly a naïve young reporter, like some of the American correspondents who just a few years earlier had made their first trips to Ireland to cover the revolutionary period. Bronner reported that he had “not heard of a single authenticated death from starvation or from typhus fever” during his travels in the west. Still, he added: “I have marveled that the people survive the hardships of their lives.”

Maine potatoes

Delegation from Maine posed outside the White House on Jan. 31, 1925, after discussing the potato embargo. Library of Congress.

Bronner’s series had particular resonance on the pages of the Bangor (Maine) Daily Commercial. In a front-page sidebar to the correspondent’s first installment, the paper alleged that British government officials had conspired with Canadian growers to block shipments of abundant Maine potatoes from Ireland. The foreigners speciously charged that the Maine spuds were infected with a common potato bug. Shortly before Bronner’s series debuted, a delegation representing Maine potato farmers traveled to Washington to lobby US Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes and President Calvin Coolidge for help to repeal the embargo.

In most newspapers that published Bronner’s series, the first installment opened with these two sentences:

Hunger sits down at table as an unwelcome and bitterly feared guest and Cold keeps him company in thousands of cabin homes today in western Ireland. That is what a partial potato crop failure and peat bog shortage mean for Galway and Donegal and Kerry and Mayo.

In the Daily Commercial, the opening text was amended to read:

Maine potatoes remain in Maine, while hunger sits down at table as an unwelcome and bitterly feared guest and cold keeps him company in thousands of cabin homes today in western Ireland. That is what a potato crop failure and peat bog shortage in Ireland, coupled with the embargo placed by Great Britain on American potatoes, mean for Galway and Donegal and Kerry and Mayo.

The Daily Commercial also denounced “the selfishness of the British government” in a separate editorial. “Our government has done all that it could and pointed out there are more beetles in the Canadian potatoes than in those of Aroostook (County, Maine), but England has persisted. And so there is unnecessary privation in Ireland, much suffering that might have been vastly alleviated.”[7]”Potato Embargo And Real Facts”, Bangor (Maine) Daily Commercial, Feb. 25, 1925.

The alleged embargo was actually part of wider and more longstanding trade problems between the United States, Great Britain and the Irish Free State; complicated in part by the 1920 partition of Northern Ireland. US officials “accepted that most members of the new (Irish) government were inexperienced both from a political and economic perspective, that the Free State was underdeveloped economically and that both industry and agriculture were in a depressed state.”[8]See the “Economic work” subsection, pp 503-526, in Chapter 12 of Bernadette Whelan, United States Foreign Policy and Ireland: From Empire to Independence, 1913-29. [Dublin: Four Courts … Continue reading Most of these problems were resolved over the coming years, but not in time to feed Mrs. Connelly’s family and other desperate residents of Ireland’s impoverished west. The inability to ship Maine potatoes to Ireland does not appear to have gained traction beyond the New England state, based on my search of US and Irish digital newspaper archives.

Other coverage

The Irish government allocated £500,000 for relief and provided 6,000 tons of coal, as Bronner and other news sources reported. An official statement insisted, “The comparison with 1847 is extravagant, and there is no general famine.”[9]”Minimize Irish Famine”, New York Times, Feb. 3, 1925. Opposition leader Eamon de Valera blamed an “English press scare” for distorting the matter, adding that a republican government would have done a better job anticipating the crisis as conditions in the west worsened during the autumn of 1924. [10]”Irish Not Starving, Declare Cosgrave”, New York Times, Feb. 1, 1925. The Gaelic American, ever the watchdog of mainstream press coverage about Ireland, also criticized British papers for exaggerating the story to embarrass the Irish government, but said nothing about Bronner’s series.

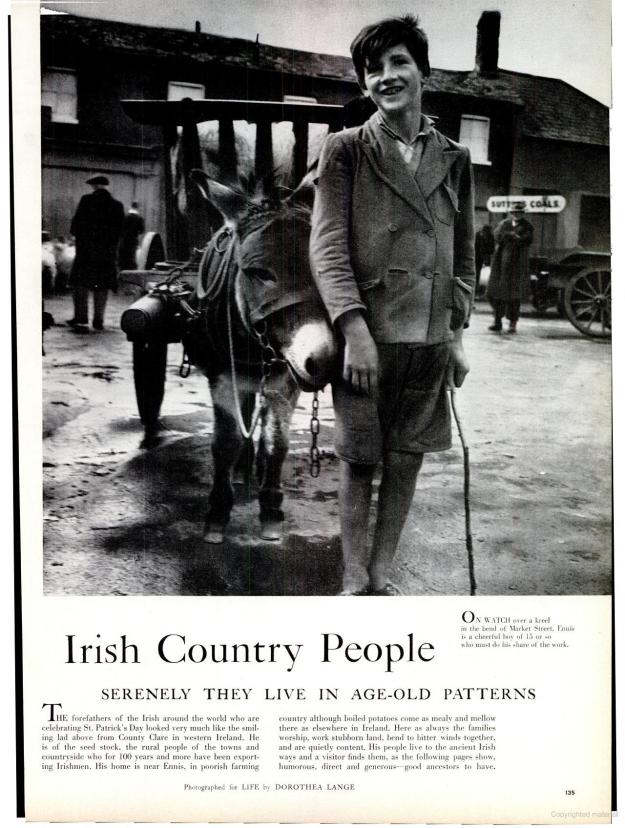

This photo also accompanied Bronner’s series in many US newspapers. Note the NEA logo in the bottom right corner, but there is no individual photo credit. It is unclear whether the boy is missing his right leg, if it is in shadow, or bent against the wall behind him.

“The Irish press gives the situation its true proportions and recognizes the efficiency of the government’s effort to meet it,” Chicago Daily News foreign correspondent William H. Brayden reported in a Feb. 7 story syndicated to other US papers. “That the situation is not regarded in Ireland with the same apprehension as abroad is evident from the fact that when the Dáil met this week and the ministers were interrogated on many subjects, no deputy raised any questions about conditions in the west.”[11]”Leader Familiar With Situation”, The Scranton (Pa.) Republican, Feb. 9, 1925.

The Armagh-born Brayden began his career at the Dublin-based Freeman’s Journal, which had folded in December 1924.[12]Felix M. Larkin, “Brayden, William John Henry“, in the online Dictionary of Irish Biography. Later in 1925 he published the pro-government booklet, The Irish Free State: a survey of the newly constructed institutions of the self-governing Irish people, together with a report on Ulster. There, Brayden wrote:

I had heard that this year the farmers were exceptionally hard hit. The cry of famine in Ireland has been uttered in America. I went to Kilkenny expecting to learn something that might confirm these tales of distress.[13]Brayden, Irish Free State … Ulster. [Chicago: Chicago Daily News, 1925], 28.

Kilkenny was hardly the place to look for food distress in 1925, as Brayden surely knew. Like the government, he downplayed the alleged famine. By summer 1925 improved weather and crop yields had largely resolved the crisis. Brayden wrote of conditions in County Clare:

A few months ago the rain had driven the people to despair of this year’s harvest and to dread another winter as bad as the last. Now the fine weather has completely altered the situation. It is declared in the county that the prospects of a successful season for the farmers have rarely been so bright. In several districts the turf supply was secured and haymaking started by the middle of June on a good crop, while the potato fields are described as in excellent condition.[14]Brayden, Irish Free State, 35.

Ireland’s “famine” of 1925 was soon forgotten.

Brayden died in 1933. Bronner remained in Europe with NEA until 1942. He interviewed George Bernard Shaw on his 80th birthday in 1936. The Irish writer told the correspondent: “Why should I let you pick my brain for nothing, when in 10 minutes I can write down what I tell you, sign it, send it to (an editor in America), and get a check for $1,000?”[15]”An 80th Birthday Message From George Bernard Shaw Who Says Proudly ‘Americans Adore Me’ “, The Helena (Mont.) Independent, July 26, 1936. A year later Bronner interviewed de Valera about the Irish Constitution. Bronner retired to his native Louisville, Kentucky.

References

| ↑1 | ”Erin Revealed As Suffering Hunger’s Pangs”, Bangor (Maine) Daily Commercial, Feb. 24, 1925. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This passage was edited shorter in some newspaper presentations of the story. Bronner reported that Bartley Connelly, the 45-year-old husband and father, was working as a farm laborer and away from the home at the time of his visit. |

| ↑3 | The 1925 Ayer & Son’s directory listed more than 22,000 periodicals in North America and US territories, including 2,465 daily newspapers. It is unclear how many NEA subscribers published Bronner’s series. |

| ↑4 | ”Milton Bronner, Reporter Retired Since ’42, Dies After Long Illness”, (Louisville, Ky.) Courier Journal, Jan. 7, 1959. |

| ↑5 | Library of Congress prints and photographs : an illustrated guide. [Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1994], 32. |

| ↑6 | These stories appeared in various US and Canadian newspapers that published NEA’s syndicated content. Search results from Newspapers.com archive. |

| ↑7 | ”Potato Embargo And Real Facts”, Bangor (Maine) Daily Commercial, Feb. 25, 1925. |

| ↑8 | See the “Economic work” subsection, pp 503-526, in Chapter 12 of Bernadette Whelan, United States Foreign Policy and Ireland: From Empire to Independence, 1913-29. [Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2006]. |

| ↑9 | ”Minimize Irish Famine”, New York Times, Feb. 3, 1925. |

| ↑10 | ”Irish Not Starving, Declare Cosgrave”, New York Times, Feb. 1, 1925. |

| ↑11 | ”Leader Familiar With Situation”, The Scranton (Pa.) Republican, Feb. 9, 1925. |

| ↑12 | Felix M. Larkin, “Brayden, William John Henry“, in the online Dictionary of Irish Biography. |

| ↑13 | Brayden, Irish Free State … Ulster. [Chicago: Chicago Daily News, 1925], 28. |

| ↑14 | Brayden, Irish Free State, 35. |

| ↑15 | ”An 80th Birthday Message From George Bernard Shaw Who Says Proudly ‘Americans Adore Me’ “, The Helena (Mont.) Independent, July 26, 1936. |