The 50th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s June 1963 trip to Ireland is getting a lot of attention. Part of the commemoration has included bringing a flame lit from the eternal flame at Kennedy’s grave in Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C. to New Ross in County Wexford.

Image from ABC

Kennedy’s trip was a triumph for Ireland, for Irish-Americans and for Roman Catholics. Thirty-two years before his 1960 election, Irish-Catholic Democrat Al Smith was crushed by Herbert Hoover in his bid for the presidency. The nation was still too mired in its prejudice against Smith’s ethnicity and faith. (As it turned out, missing the 1929 stock market crash and start of the Great Depression might have saved Irish-American Catholics further hatred in the long run. It sure helped the Democrats.)

As Kennedy made his historic visit to Ireland in June 1963, a small group of Pittsburgh-area politicians and volunteers established the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum. They realized that street railways in Pittsburgh and other parts of the nation were fading from regular use as buses became the preferred public transit to serve far-flung, rapidly growing suburbs.

What does that have to with Kennedy?

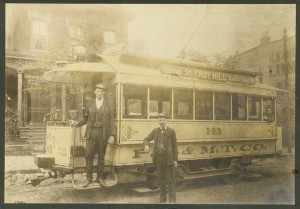

Irish immigrants dominated the labor force of street railways in urban America from the time the systems were created in the late 19th century. They joined the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees, formed in 1892, to push for higher wages and better working conditions.

“The streetcar workforce and the union were composed entirely of men, many of whom were Irish,” says the National Streetcar Museum in Lowell, Mass.

The same was true in other Irish immigrant hubs such as nearby Boston (where Kennedy’s ancestors settled), New York, Chicago and Pittsburgh. My Kerry-born grandfather, his brother-in-law and three cousins were among many Irish immigrants employed by Pittsburgh Railways Co. as motormen and conductors.

Like cops, the Irish had a big advantage over other immigrants in obtaining these big city jobs, which required frequent public contact. They spoke the language. In both professions, these unionized, uniform-wearing jobs helped first-generation Irish immigrants build middle-class lives that provided even better opportunities for their children and grandchildren.

And that’s another important part of what JFK’s trip to Ireland symbolized in June 1963.

Early 20th century Pittsburgh Railways Co. streetcar workers.

DISCLOSURE: I am a member of the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum.